My Favorite Jane Austen Scene by Harry Frost

- Christina Boyd

- Jul 14, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jul 15, 2025

This year marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth—a milestone that invites both celebration and reflection. Two and a half centuries later, her world remains irresistibly alive. Austen’s sharp wit, enduring characters, and quietly radical storytelling still resonate, drawing readers into her spellbound orbit. The devotion extends far beyond The Six, spilling into countless adaptations, retellings, and tributes that span bookshelves, screens, and even pilgrimages through the English countryside. Her legacy endures not as nostalgia, but as a living force.

So, what is it about her work that continues to speak to us, generation after generation?

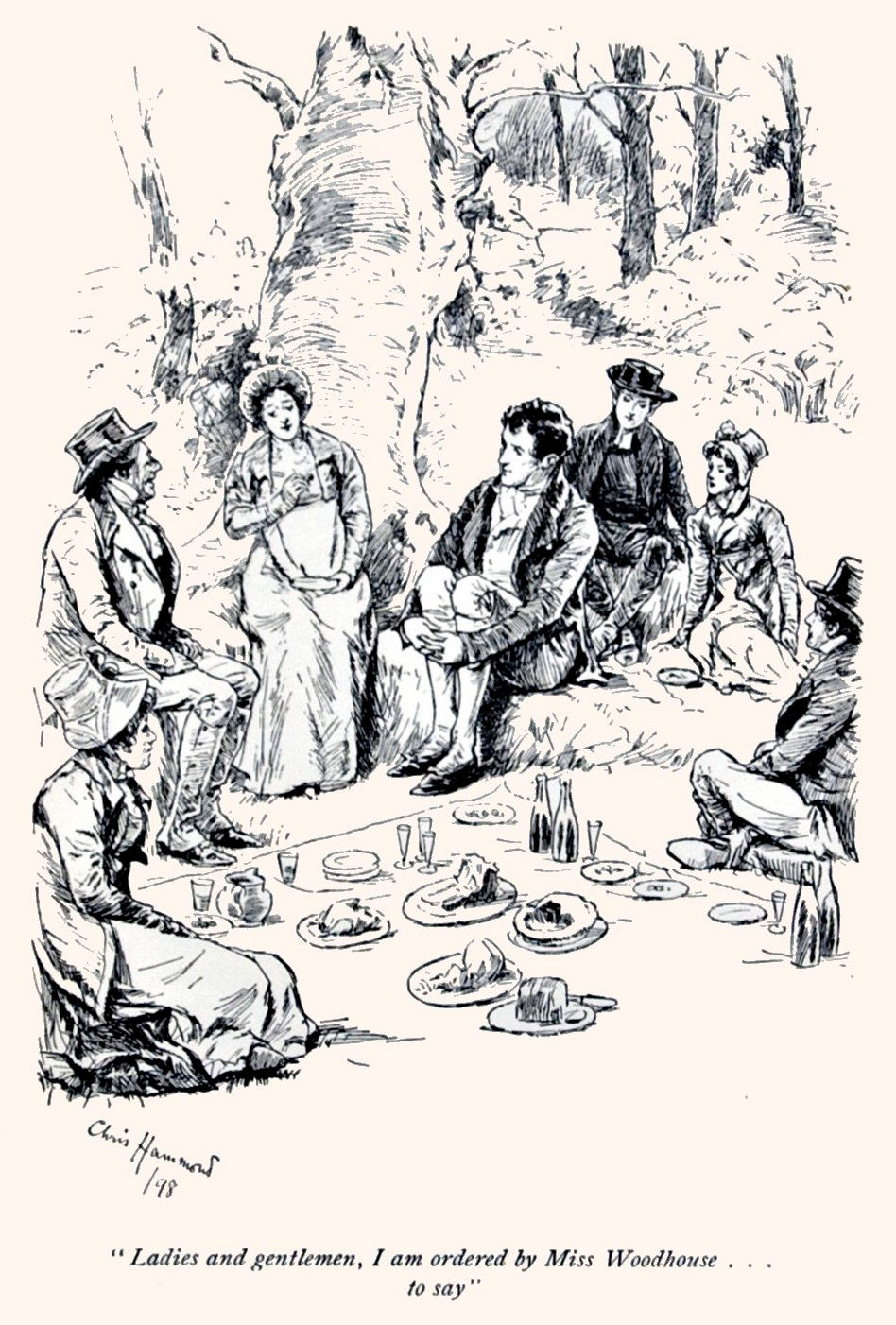

To explore that question, I’ve asked some of my favorite Austen authors, readers, and scholars to share the moments that sparkle, ache, or linger long after the final page. Together, we revisit the flashes of brilliance—quiet or bold—that make Austen’s voice as vital today as it was 250 years ago. This month, I welcome one of my favorite British narrators, Harry Frost, who shares his favorite scene from Emma, The Box Hill Picnic (Chapter 43). I am delighted he has also offered a narration for this piece.

You can listen to him here, by clicking the above image, or on YouTube.

‘[Miss Woodhouse] only demands from each of you either one thing very clever, be it prose or verse, original or repeated — or two things moderately clever — or three things very dull indeed, and she engages to laugh heartily at them all.'

'Oh! very well,' exclaimed Miss Bates, 'then I need not be uneasy. 'Three things very dull indeed.' That will just do for me, you know. I shall be sure to say three dull things as soon as ever I open my mouth, shan't I?

Emma could not resist. 'Ah! ma'am, but there may be a difficulty. Pardon me, but you will be limited as to number — only three at once.'

By Harry Frost

I don’t exactly love this scene. In fact, it haunts me. The genius of Austen—to make her stories feel real in ways that, because emotional rather than circumstantial, ring as true today as when they were written—cuts both ways. I’ve been at my share of Box Hill picnics as a teenager. The mantra of my social anxiety became, to adapt a poker expression: “If you don’t know who the Emma at the picnic is…you’re the Emma”. The times I was…was nearly…might have been…make for exquisitely unpleasant, sleep-postponing viewing in the cinema of memory.

There is a stage in child development when a baby can distinguish themselves from the other people they see around them. They develop the concept of self. There is then a much later epiphany, maybe a decade of them, larger or smaller, by which we realize that how we perceive ourselves doesn’t match up with how others perceive us. By extension—since what is behavior but the self-offered up for the judgment of others?—we realize our actions might give the lie to our own self-image.

For Emma, this second epiphany comes late. In a working family of the time, such things were addressed the moment young Billy proclaimed, aged five, “You know, Father, I don’t believe I shall crawl inside a piece of industrial machinery today; I should rather stay home and eat cake.” Emma, however, is shielded by her wealth and position. She has many privileges (and so needs nothing from anybody) and few responsibilities (nobody appears to need anything from her, though they impertinently want plenty).

Emma considers herself virtuous. She cares for her father, she plays and sings, she helps others. We, the readers, know that her mere presence is all the care her father requires, that she doesn’t apply herself to her accomplishments as she might, and that she is highly selective as to whom she hands out her advice—which is, in any case, of doubtful utility. Yet, from a modern perspective, it is hard to say where she goes wrong. Our societies have become fabulously wealthy by Regency standards, our irresponsible childhoods and adolescences longer on average, and our culture increasingly atomized. Morality—setting religion aside (as is widely done)—is now much less socially than legally constituted: “as long as you don’t break the law, you’re probably all right” is a reasonable dictum.

Emma didn’t break the law. All she did is make a joke at the expense of a rather dull woman, who practically invited it. It was actually pretty witty. Emma didn’t even want to play the silly game that started it, Frank Churchill suggested it because he was bored. And Mrs. Elton really was insufferable, with that remark about knowing when to hold her tongue; as if she ever did herself. And Mr. Weston covered the moment immediately afterwards…

So, we must suppose, go Emma’s rationalizations as she replays the incident again and again for who knows how many years afterward. But she knows very well what she did, even before Knightley spellsit out. Like Darcy, like Elizabeth, in their story, she awakens to the fact that she has done wrong by her own definition, such that even lesser characters, even the comic relief, look comparatively virtuous at that moment, and Jane Fairfax (simply by saying nothing)remains a paragon, for all that it’s Emma’s name on the dust jacket (Emma is surely “Patient Zero” of “Main Character Syndrome”).

It wasn’t what she said. It was that she, Emma, said it, and to Miss Bates. Nothing makes it better, not the truth of the insult, not Churchill’s pot-stirring, not the Eltons’ gaucheness. And the worst thing is, no matter how mortifying it is for Emma, she knows it’s ten times worse for Miss Bates who, as an impoverished gentlewoman, has nothing but her social standing left, and who has been insulted publicly by a girl many years her junior, who only holds the influence she does because she is handsome, clever, and rich.

On such things the plots of our lives turn, our arcs realign. Emma claws it back, I (somehow) made it through my teens. Both of us woke up to the fact that there is no “opting out” of society and, as with taxes, ignorance is no defense. If we don’t think we have any social responsibilities, that’s what we’re doing wrong for a start: not knowing.

Austen gives us plenty of happy mantras to hang onto. “Only think on the past as it brings you pleasure.” “Know your own happiness.” Yet those less happy are no less useful. If one reads of her early enough, perhaps Emma endured this bad picnic that we might only have good ones.

ABOUT Harry Frost, Voice actor and writer

Former boarding school scholarship boy, my voice is 100% genuine British RP. I got my BA in Literature in 2010 from the University of Exeter and, of course, instantly got a job in a cocktail bar. Then, I was a market analyst and took a master’s in economics and international Relations in 2018 before finding narration full-time. My repertoire includes 134 characters and counting, and I speak Italian, French, and a bit of German.

My wife Jade and I live with our daughter in the English countryside. She’s the center of our world, and I absolutely adore her. She gets a heavily discounted rate on bedtime stories.

*Connect with Harry via his website.

%20(1).png)

Thank you, Harry, for sharing this heartfelt piece. I had never really analyzed the Box Hill scene like that. I don’t think I will be able to think of it without considering your emotive perspective again.